Written by: Donata Henry, Dauphine Sloan, Thomas Hebert, Michael Joyce, Christine Smith, and Toni Weiss

Teaching a large class poses unique opportunities and obstacles, both in and out of the classroom. Large enrollments can expose students to a diversity of opinions and provide a platform for enhanced student learning. However, an instructor must be aware of the numerous challenges of increased class sizes. For instance, how does one best manage the daily administration of what can often feel like a small city? Below are strategies to assist instructors in the following areas:

How to encourage students to participate in large classes?

Research has clearly shown that the traditional lecture format of teaching does not promote student engagement, especially in large classes. However, it can be very challenging for instructors to incorporate active learning techniques in large classes. So, what can be done to remedy this problem?

Instructors should make it clear during the first weeks of class that they expect students to question them and interact during class. They can introduce questions and exercises that ensure that interaction is constructive and safe. It can be helpful to break up the class into 10-20 minute segments, incorporating a specific question or exercise that requires student participation in each segment. The questions or exercises can take several forms:

Faculty move! - Standing in the front of the classroom maintaining a distance between the instructor and the student by definition is not promoting student engagement. Walking through the class (up the aisles, in the back, even occasionally sitting next to students, etc.) infuses energy and movement into the room, thereby increasing the probability of learning vs. a static environment. There are technologies, such as Doceri, that allow instructors to untether from the podium and walk among students in the class. An additional benefit of Doceri is the ability for students to actively engage with their classmates (i.e. solve problems, draw graphs, etc.) from the safety of their seat.

Think-pair-share - In this simple exercise, the instructor poses a question or problem to the class. After giving students time to consider their response (think), the students are asked to partner with another student to discuss their responses (pair). Pairs of students can then be asked to report their conclusions and reasoning to the larger group, which can be used as a starting point to promote discussion in the class as a whole (share). This exercise helps promote engagement because students feel greater responsibility for participation when paired with another student. In addition, the inclusion of “think” time and the initial opportunity to “practice” a response with a single peer reduces the anxiety some students feel about responding to instructor prompts. This technique can be used with with a classroom response system such as Turning Point.

Minute paper - Students are asked to spend one to three minutes writing the main point of the prompt as well as identify any questions that remain in their mind. These papers can serve multiple purposes: they can be used by the instructor as a formative assessment (see Handling Student Grades section), they can serve as a tool to promote metacognition (asking students to consider what they do and do not understand), and they can be used as the basis for small or large group discussion. Most importantly, however, they are a great tool for the instructor to assess whether learning is occurring. As with the think-pair-share technique, the minute paper gives students time to compose and articulate their thoughts, increasing their comfort with asking questions or entering discussions.

Muddiest point paper - This modified version of the minute paper asks students to articulate the point that is most unclear to them at a given moment in the class. It serves the same functions and has the same potential uses described for the minute paper.

Clicker questions - Questions that can be presented as multiple-choice questions are particularly amenable to use with a classroom response system such as Turning Point, or classroom response systems. All students in the class are asked to choose a response to the question, and the results can be displayed in real time. If the instructor wishes, student responses can be tracked, either to serve as an attendance measure or as a formative assessment (see Handling Student Grades section). This technique has the benefit of broad student participation. In addition, clicker questions can be used to foster discussion very effectively; if a significant fraction of the class answers incorrectly, then student groups can be asked to discuss before re-voting.

Small group activities - Studies suggest that small-group activities promote student mastery of material, enhance critical thinking skills, provide rapid feedback for the instructor, and facilitate student self-efficacy and learner empowerment. Instructors can allow students to choose their own groups or assign groups either randomly (i.e. using playing cards) or sorting by individual student competency levels. Assigning group members’ roles (like facilitator, recorder, divergent thinker, etc.) or distributing a group assessment rubric can keep groups relatively balanced and fair and help ensure participation by all group members.

Discussion boards - One of the most useful features of Canvas is the discussion board feature. Integrating an online discussion board into the classroom experience is a great way to provide structured opportunities for quieter students to participate in the course. Additionally, it can be particularly valuable in large courses as many students might have wonderful things to contribute yet receive comparatively fewer opportunities to do so. Consider posing online discussion questions before lessons to get students thinking about the material before class, or asking students to respond to discussion questions after class to demonstrate their synthesis of the material.

How to foster a welcoming learning environment?

There is much that instructors can do to project a demeanor that promotes student participation in large classes.

Make it a priority to learn and use student names - Some instructors use tent cards or the class list from Gibson Online which includes students’ pictures to facilitate learning student names. This practice helps ensure a broad base of participation and makes students less likely to disengage during class. While this is an ideal practice, the number of students in the class may make this impossible to achieve…. Don’t beat yourself up!

Establish a rapport - At the beginning of each semester, some instructors ask students to fill out note cards describing some of their interests. By looking over these note cards and memorizing student names, instructors get to know their students and may even greet them by name and speak with them as they enter the classroom. Such efforts often result in a better rapport between professor and student, and as a consequence, a more engaged classroom.

Be patient and affirmative with students in class and out - These behaviors can bolster student confidence, and more confident students are much more likely to participate in class. No matter how busy you are, it is imperative that you are present when you encounter students. You can demonstrate this by maintaining eye contact, not checking email, inquiring about their general wellbeing, etc. Additionally, while student questions may seem unnecessary, repetitive, and/or obvious, they must be met with a respectful, thoughtful response.

Develop strategies to encourage students to use office hours - Some instructors require students to meet with them in small groups for about five minutes, during the first few weeks of the semester. This brief social interaction helps to remember students’ names and makes students more comfortable and class interaction easier.

Show up early for class and greet students as they enter the classroom - Having a friendly conversation about their weekend plans, teams they participate in, etc. may make them more willing to ask content questions during class.

How to encourage positive peer interaction?

It is critical that instructors promote an environment of trust and mutual respect from the very beginning of the course. In such an environment, students are more likely to feel safe to actively participate in class. The idea is to foster a sense of personal connection between students and instructors through group and partner activities that help students get better acquainted. The resulting feelings of cohesiveness are especially valuable because students who feel that connection are far less likely to go against their classroom community’s norms. Finally, instructors should be sure to balance student voices by soliciting opinions from a variety of students across the classroom – rather than a few dominating voices – and by protecting those speaking up from interruption.

All of the approaches described above allow students the opportunity to engage with class questions and challenges anonymously or in small groups instead of or prior to large class discussion. These tools can therefore reduce student fears and thereby promote participation. In addition, online discussion boards can provide structured opportunities for students who are more reserved to participate in class discussion.

Large classes come with grading challenges familiar to instructors across a range of disciplines. A certain number of assessments is necessary to ensure a fair grading system, including timely, meaningful feedback. However, there are time constraints. Is there a way to strike a balance without relying entirely upon multiple choice exercises? Absolutely.

Formative Assessments

Formative assessments are generally low stakes, which means that they have low or no point value. They serve to engage students and provide timely feedback to both students and instructors. There are several ways to incorporate more formative assessments into the classroom that do not add significantly to instructors’ workload. Short quizzes, polls, homework, in-class problems, and discussion-oriented activities in the classroom enable students to practice course-related skills and demonstrate comprehension of the material, while not requiring time intensive grading.

Such activities provide students with valuable verbal (and sometimes written) feedback from professors, TAs, and other students. Feedback-providing activities are especially valuable in classes in which the first graded assignments may not be returned to students for several weeks. Some examples include:

Polling technologies - Turning Point can provide immediate feedback and help define expectations for student performance.

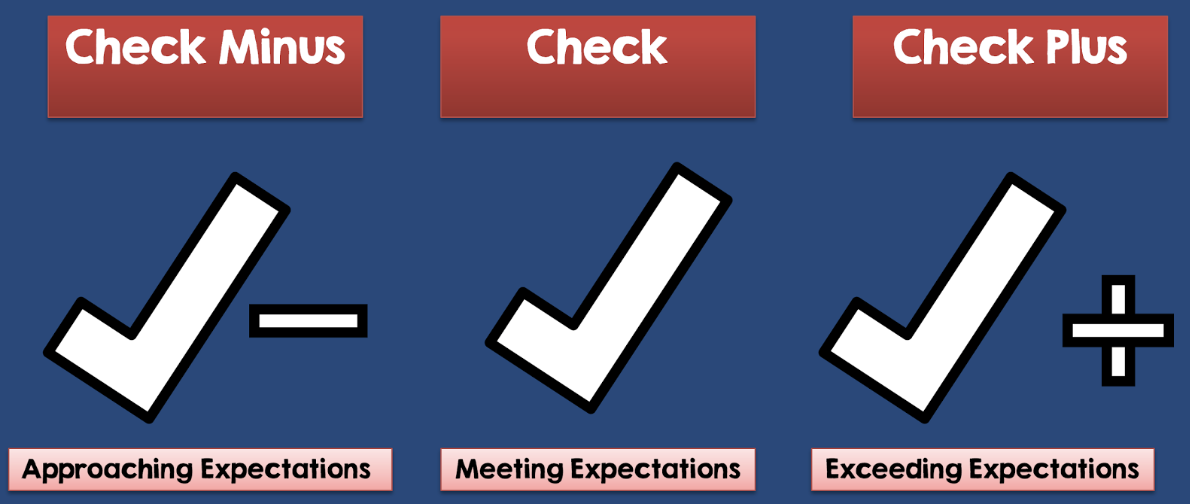

Short assignments - Journals, Discussion Boards, etc. can be graded on a 3-5 point scale, with specific pieces of information required for each point. Alternatively, a system can make the grader’s job quicker and easier while providing feedback to instructor and student alike. It is important to realize that there is no need to grade everything on a 100-point scale with copious comments.

Automated grading - Homework and quizzes, whether built into Canvas or provided by textbook publishers, requires minimal instructor time.

Attendance/Participation - Points for attendance and/or participation can extrinsically motivate students to engage actively. Consider using Arkaive or a classroom response system such as Turning Point.

For additional techniques, see Promoting Student Engagement and Integrating Technology.

Summative Assessments

The goal of summative assessments is to evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional unit by comparing their individual performance to the established learning outcomes. Summative assessments are often high stakes, which means that they have a higher point value. Examples include exams, group projects and papers. For large classes, the grading of these assessments can be onerous for the instructor and/or TA. As such, the default is often to rely strictly on multiple choice tests. However, not all disciplines lend themselves to this testing format and it is not always the optimal means of assessing student learning. Below are some strategies to facilitate grading for non-objective major assessments in a large class.

Tests/Exams - The thought of administering and grading non-objective tests/exams in a large classroom can be daunting. One might consider, however, that there are ways to build in subjectivity without over burdening the grader. For instance, prompts that require short responses (one or two sentences) can quickly assess student learning. Alternatively, asking students to choose two out of four (for example) problems or short essays, can decrease grading time. The added advantage of this strategy is that not all students will choose the same questions to answer, thereby reducing the “brain-numbing” effects of grading 200 of the same response.

Groups - While most instructors see the value in projects and papers, how can this type of summative assessment be carried out in a large classroom? One option is to split students into groups. For instance, in a class of 200, placing the students into 50 groups of 4 cuts the grading load, while still giving students a chance to practice their skills and receive feedback. Such group work also has value in promoting the kinds of communication skills necessary for critical learning.

To help promote active contribution by all group members, consider implementing one or more of the following:

- Have students work in groups on smaller, low-stakes’ formative assessments so that they can navigate group challenges without the penalties of group members not pulling their weight.

- Assign each member of the group a specific role.

- Have group members exchange roles, and/or serve in each role at some point during the project.

- Build a peer review element into the final assessment so students feel accountable to one another. One suggestion is to have each member of the group identify team members who are the “most helpful” and “least helpful.” The instructor can then add or subtract points from the identified students’ grade if the outcome is unanimous.

Grading Tools

Rubrics - A rubric is a scoring tool that explicitly represents the performance expectations for an assignment or piece of work. It divides the assigned work into steps. Each step outlines clear descriptions of the characteristics of the work and a rating scale indicating the varying levels of mastery.

Using a detailed grading rubric for papers and other assignments can streamline the grading process and reduce the need for extensive written comments. Rubrics can also obviate problems of inconsistency when working with more than one grader, such as TAs (see Working with Teaching Assistants section). Canvas that appear in the right sidebar in the Speed Grader tool. The rubric will automatically tally the points you assign and provide a comment box for each criterion. Rubrics can be saved and reused in subsequent courses.

Comments - One of the most time-consuming aspects of grading in any classroom is providing comments on student papers, all the more so in a large class. Often, instructors make the same comments over and over again on many papers. Rather than repeating those comments in full sentences, consider distributing a “key/legend” of your shorthand comments. It is recommended, however, that you still include one comment on each assessment that conveys personalized attention.

In addition, Canvas has many tools built in to its grading function to improve efficiency such as Speed Grader, audio comments and video comment.

Handling Grade Complaints

In most classes, large or small, grade complaints are inevitable. However, the issue can become more pronounced when a couple of upset students becomes a dozen or more. How can instructors best deal with grading complaints?

Have a formalized system in place - Instructors of large classes approach grade complaints in a variety of ways. Some insist that students come directly to them with their concerns. Others suggest that undergraduates speak to their TAs first before consulting the instructor. Still others give full authority to their TAs to handle all grade complaints. The important thing is to have a formalized system, preferably outlined in the course syllabus. Students should know upfront what is expected of them, and what their options are if they feel they have been graded unfairly.

Require complaints to be written and submitted - One common technique to avoid frivolous grade complaints is requiring a written explanation of the complaint at an early stage. Oftentimes, upon writing their complaint, students realize that the grade was actually deserved. Indeed, this exercise forces them to reflect upon the written comments on their exam or paper, not just the grade itself.

Institute a 24-hour rule - Another way to ensure that students are carefully considering the grade and comments and are not simply going with a visceral reaction is to have a 24-hour rule. Students are required to take 24-hours before contacting the TA or professor with a grade complaint. This 24-hour period often serves as a “cooling off” period in which students can read and think about graders’ comments.

Another common challenge for instructors teaching large classes is the management of graduate teaching assistants (TAs). TAs are often tasked with grading in large classes, but they come to that activity with vastly different conceptions of what effective grading looks like and how it can be accomplished in a reasonable amount of time. Likewise, TAs come with different teaching skill sets and life experiences. Some of them are mature, effective teachers, while others are preparing to teach their first class. In large classes, these issues are often amplified by the number of TAs required. Below are some strategies to consider:

Grading

One common complaint in large classes concerns inconsistency in grading. Most instructors will recognize the refrain, “My TA is an unfair grader! Can I change sections?” Indeed, it can be frustrating for students who believe that they are the victim of the “tough grader,” and are receiving worse grades than their friends despite handing in comparable work. So, how to ensure consistency and mitigate student charges of unfairness? For additional information see Handling Student Grades.

Have regular grading meetings with your TAs – The best way to promote grading consistency among TAs is to meet as a group soon after collecting an exam or paper. It is unfair to assume that our TAs will simply know what we are looking for on any given exam question or paper topic. If grading essays, identify and photocopy an exemplary essay, a few mediocre essays, and a poor essay and distribute these essays to each member of the group. Prior to the meeting, have each TA grade and comment upon these essays. At the meeting, go through each essay one-by-one. Ask each person what grade they gave to each essay and why. Ask them about the best and worst aspects of each piece of writing. Such a meeting provides a wonderful opportunity for graders, especially those who are less experienced, to think about how they are approaching their grading. It can serve to calibrate expectations for the exam or paper. The meeting can also serve as a forum for instructors to explain their expectations for exams and papers.

Use grading rubrics - A carefully designed grading rubric can both minimize the amount of time spent grading, an important consideration in large classes, and serve as a common standard for TAs. TAs could even help construct a grading rubric. Such an exercise can be valuable to them because it facilitates the grading process, but it also gives them an opportunity to play a major role in student assessment, a valuable experience for those TAs who hope to teach courses of their own at some future time. It also gives instructors a new and unique perspective on class exams, papers, and assignments that may ultimately enrich the course. Rubrics can be created in the Speed Grader’s right sidebar on Canvas. The rubric automatically tallies the points assigned and also provides a comment box for each criterion. Rubrics can be saved and reused in subsequent courses.

Divide up grading sections - Better consistency can be ensured by assigning specific questions of the exam, across classes, to the same TA (i.e. Question 1-3 is graded by “TA Jones” across all sections of the course). This is more challenging with essays, but is a common approach for grading exams. What this technique entails specifically depends on the exam’s makeup, but for example, one TA could grade the short-answer section, a second TA the first essay, and a third the second essay. While there still may be inconsistency between questions, using this method prevents students from arguing that their particular grader is tougher as each exam is graded by multiple TAs.

Managing TAs Who Lead Discussions, Lab Sessions, and Review Sessions

Know Your TAs - Just as with grading, TAs come to discussion-leading with different levels of expertise. Some will be at home in the classroom. Others will be terrified to speak in front of their students. It is a good idea to get a gauge on this in the weeks preceding the semester so that TAs may be given the appropriate level of support. Some may be independent and will desire considerable control over what happens in their classrooms, and others may require strong guidance. Thus, one ought to get to know one’s TAs.

Hold regular meetings - Regular weekly or bi-weekly meetings can be valuable to provide a strong support system for TAs and maintain some control over discussion, lab, and review sessions. These meetings can serve many purposes. This time can be used to go over important concepts and course content with the TAs who do not have extensive teaching expertise. This can also be a useful “check-in” period to get a sense of how the course is going for TAs and students alike. These meetings can also be a forum in which TAs are provided with handouts or discussion guides to help facilitate their class time and provide a support structure in which everyone can talk through issues relating to the class.

Cheating may exist in college courses of all sizes, but in large classes, it can be particularly challenging to identify it when it occurs. As anyone who has proctored an exam for 100+ students can attest, it can be very difficult to monitor almost “city-sized” courses. So, what can be done?

Be upfront with expectations

Although many students may be able to articulate a definition of plagiarism or cheating, they may not be so clear on what actions constitute this in each of their different courses.

Students may have read portions of the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct during orientation week and are likely familiar with black and white scenarios (i.e. copying answers off of their neighbor’s exam is cheating). Do they know, however, what constitutes an honor code violation in those grey and murky scenarios that sometimes confront them?

- What are instructors’ expectations for open book/note and/or take-home exams?

- If students are allowed to work on homework assignments in pairs or groups, are they allowed to hand in comparable or identical assignments?

- How should students cite sources in their papers? Is a works cited and/or bibliography page required?

Instructors need to anticipate such questions. Before assigning or administering any assessment (i.e. homework, quiz, paper, test, exam, etc.), they ought to have a conversation with students about their expectations. Ideally, they should clearly outline those expectations in writing in the syllabus, so students may refer to it throughout the semester. Putting those expectations in writing also helps instructors in the event they need to charge a student with a violation of the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct. Some instructors even choose to dedicate early class time to giving their students a tutorial on cheating and plagiarism. In addition, instructors should review their assessment policies throughout the semester.

Rather than dealing with cheating and plagiarism issues in a reactive manner, instructors need to be proactive. People are tempted to cheat when the stakes are high. Instructors can incorporate a variety of assessments into their course, thus reducing the weight of an individual assignment, paper, test, etc. This may reduce the incentive/pressure for students to cheat.

Dealing with cheating on exams

Trying to identify students actively engaging in cheating can be challenging, but consider the following strategies:

Proctoring effectively - On the surface, proctoring can seem like a very basic exercise: watch the students as they take the exam and make sure they are not communicating or looking at one another’s tests. However, there are some aspects to proctoring that are easily overlooked. For example, you may want to consider the following:

- If possible, have a minimum of 2 proctors - Part of the proctor’s role is often to field student questions during the exam, but while the instructor is answering that question, who is observing the students?

- Require students to remove hats with brims - Instructors may require students to remove hats that cover their eyes or put them on backwards, if possible.

- Require that all electronic devices (phones, tablets, watches, computers, Fitbits, etc.) are turned off (not just in “silent mode”) and stowed away (not on the student’s person but in a back pack, front of the room, etc.).

- Do not allow students to leave the room once the exam has been distributed – This prevents students’ from storing notes in restrooms or communicating with others outside of the classroom. Of course, this does not apply to students with specific accommodations.

Randomize the blue books - In some large classes, students use blue books for exams. Students are typically asked to bring these blue books with them to class on exam day, especially in large classes where the instructor would have to pay a considerable amount of money to provide all students with exam booklets. Some students see this as an easy way to cheat by writing answers in the blue book and referring to them throughout the exam period. One possible solution is to ask students to hand in their blue books as they walk in the classroom, shuffle, and then redistribute them to students randomly.

Randomize the exams - Perhaps the most traditional way to cheat on an exam is for a student to copy off of his or her neighbor. The easiest way to avoid this is to administer multiple versions of the exam. This includes randomizing the question order, the numbers used in a fact pattern, and the answer options. Some professors print multiple version exams on different color sheets of paper to further confuse a student who might like to copy his or her neighbor’s exam.

Randomize the seating - In many large classes, it is not always possible to leave spaces in between each student. However, students can be required to sit in every other seat as they come in. As subsequent students arrive, they must fill in the empty seats. This may help to prevent friends who arrive together from sitting together.

Revise exams each semester - Designing tests can be a time-consuming affair. For that reason, some instructors use the same test questions year after year. While this is tempting, it is not advisable if striving to prevent cheating. Some student organizations keep files of past exams for a variety of courses. Exam questions should be changed each semester to prevent students from having an unfair advantage. For those instructors who do not return exams, this is still an advisable practice as the specific content covered each semester may vary and the relevance of the assessment must be ensured.

Dealing with cheating on papers

Identifying cheating on papers often requires knowledge of a student’s writing abilities. For example, when a student who has historically struggled with writing submits a flawless paper, an instructor may have good reason to suspect cheating has occurred. In large classes, however, it may be difficult to have a sense of students’ writing skills and ability, so what can be done to stop plagiarism?

Provide students with clear instructions - Again, setting expectations is a key factor in helping students succeed in this area. Many students are inexperienced when it comes to writing papers, citing sources, etc. How should they cite their sources? How thoroughly? Will parenthetical citations suffice? What citation style is preferable? Is a bibliography or works cited page required? These types of questions should be clearly addressed in the course syllabus and assignment instructions.

Use Turnitin - Canvas allows users to choose whether or not to run student assignments through “Turnitin,” a program that checks for plagiarism, generates feedback for students on revision strategies, and serves as an online platform for instructors to provide electronic feedback to students. To use Turnitin, instructors must select the option “enable Turnitin” for each individual assignment that they would like to run through the tool. For further instruction, see the following Canvas Guide.

So, a student is caught cheating. Now what?

There are a number of ways that instructors can approach a violation of the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct.

Meet with the student - Before an instructor decides to pursue the formal violation process with the Honor Board, meeting with the student and asking them about what happened can be valuable. Students often appreciate the opportunity to discuss the alleged violation and the meeting can provide the instructor with an opportunity to assess the veracity of the student’s claims. Sometimes the issue is simply a miscommunication or misunderstanding that can be handled between instructor and student.

Ask the student to redo the exam, paper, or assignment - It is within the discretion of the instructor to ask students to redo an assignment if the violation is minor. This is an opportunity to use the education process to imbue a sense of civic and individual responsibility. Requiring an additional deliverable (i.e. a reflection paper, essay, etc.), identifying what they did wrong, why it is wrong, and what corrective steps they will take would be appropriate. It is, however, strongly discouraged to simply give the student a zero on the exam, paper, or assignment. The student may file a complaint against the instructor if they are denied any kind of due process in an accusation of cheating.

File a formal violation of the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct - If the instructor decides to file a formal violation, visit the Newcomb-Tulane Code of Academic Conduct website.

Large courses come with a number of logistical issues that can be challenging if instructors are not prepared to handle them. How do they keep their email boxes from filling with student messages 24 hours before an exam? How do they manage the line of students that might develop outside their office during office hours? Many of the logistical issues associated with a large class can be addressed by making rules and expectations for students clearly known beforehand.

Taking Class Attendance

While many instructors do not take class attendance in their large classes, some do. But how can one best take attendance in a large class? One might be tempted to rely upon an attendance sheet that is passed around the room, however, this may result in more work for the instructor. The sheet can get lost, students might sign in for one another, and for this to be effective, data needs to be transferred. Alternatively, instructors can take attendance through the use of Arkaive or a classroom response system such as Turning Point. Brief in-class assignments or quizzes can also be valuable in taking attendance. One can ask that students answer a day-related prompt on a note card at the end of class, sign it, and hand it in before leaving. This note card can be graded or not and can be worth points or not, however, as noted above, for this to be effective, the instructor must transfer the data.

Managing Student Email

When teaching a large class, the number of student emails can seem overwhelming. While it is encouraging that students are engaging their professors and seeking information/assistance, the logistical and time challenges need to be managed. What can be done?

Consider setting up a separate email account specific to that course - Funneling all class emails to one account, separate from your primary inbox, ensures that student emails will not “slip through the cracks”. Additionally, the instructor can check it once a day and easily answer each email without having to search through a cluttered inbox. Further, this task can be assigned to a graduate/teaching assistant who can answer the routine questions while forwarding the instructor anything that requires their specific attention. For more information call the Technology Help Desk at (504)-988-8888.

Be upfront about how often student emails will be checked and answered - Undergraduate students have grown up in an age of technology in which many of them expect immediate responses to their emailed questions, big or small. This unreasonable expectation can be mitigated by clearly outlining your email response policy in your syllabus. For example, “I will read and respond to student emails once per day, each morning” or “Please give me 24 hours to respond to each email.” Such guidelines can help avoid rapid fire emails from students. Students also may be more inclined to think ahead with their questions and concerns knowing the professor will not get back to them immediately.

Communicate guidelines about the type of questions best answered via email vs. office hours or direct communication with the instructor - Some questions lend themselves to quick emailed responses, others do not. It may be valuable to tell students what kinds of questions can be effectively answered via email and which are better left for office hours or in class Q&As.

Manage predictable email volume - The 24 hours prior to a major assessment such as an exam or paper, is often a time of increased numbers of student emails. It is important to remind students that instructors do not “keep the same hours” as they do. Therefore, an email sent at 2:00 am the night before a 9:00 am exam the next day may go unanswered. On the other hand, instructors should be aware of this increased flow and plan accordingly.

Managing Office Hours

Encourage students to utilize their TAs - TAs are capable of handling many student issues, and there are some issues for which TAs are actually better suited than instructors (for example, for discussion section or lab questions). Make sure that your TAs are available for office hours and encourage students to visit them with their questions, particularly when instructors are unavailable or otherwise too busy (remember, not all student questions/issues are appropriate for TAs and should be handled by the instructor). Have the TAs’ contact information and their office hours’ schedule included on the syllabus. Additionally, ask your TAs to email the class via Canvas to encourage them to attend all office hours.

Lay some ground rules for office visits - Sometimes, in the days (especially the day) preceding an exam, students will visit instructors during office hours, expecting to hold an hour-long one-on-one study session. This could certainly be valuable for the one student; but it also might impinge on time constraints as the instructor needs to be available for many other students. If the instructor does not want to hold last minute extended one-on-one reviews, then a dedicated review session or inviting more than one student at a time into office hours may be more efficient (before doing so, confirm with students that no one has a private matter to discuss).

Create an office hour sign-up sheet with individual appointment times - Being an instructor of a large course sometimes means managing more eager office hour visitors each week than with a small course. Without individual appointment times, student arrivals might overlap and students will mill around outside your office waiting their turn. This is not only an issue for office neighbors; it is not a valuable use of students’ time. Consider implementing a formal office hour scheduling system, such as the one available in Canvas.

Consider holding online office hours - If scheduling weekly office hours is difficult, or if there is a need for more, an instructor may choose to hold online office hours, for instance via Zoom. While this may feel awkward to instructors, most students are used to and comfortable with interacting in this space.

While some instructors view new technologies with a suspicious eye, students expect them to be integrated into their learning experience. More importantly, for those teaching large classes, certain technologies can drastically improve the quality of the instruction, and the student and faculty experience. Throughout this guide, many technology tools and their applications are discussed. Below is a quick reference of those discussed:

CELT maintains a lending library with many volumes on this subject. Some examples are:

-

Angelo, Thomas A. & K. Patricia Cross. “Classroom Assessment Techniques”, 2nd edition, Jossey-Bass, 1993.

-

Heppner, Frank. “Teaching the Large College Class: A Guidebook for Instructors with Multitudes”, 1st edition, Jossey-Bass, 2007.

-

Lang, James M. “Small Teaching: Everyday Lessons from the Science of Learning”, 1st edition, Jossey-Bass, 2016

-

Nilson, Linda B. “Teaching At Its Best”, 3rd Edition, Jossey-Bass, 2010.

We greatly appreciate the work done by Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching on their guide, “Teaching Large Classes”.

Click here to download/print the Teaching Large Classes guide.